|

I'm very fortunate to have been awarded some research leave for this coming autumn term. That means I'll be focused on a number of writing projects for the rest of 2021 and for the most part resisting invitations to speak or interview or write other things. I've got three books in particular that I hope to finish. These are:

Here’s a quick round up of online talks I’m giving this autumn, along with links:

1. ‘What is Stoicism?’ at Stoicon, Saturday 17th October, register at https://www.eventbrite.ca/e/stoicon-2020-virtual-conference-tickets-103616048390 2. 'Stoicism and Social Media', The Aurelius Foundation Webinar, Friday 30th October, register at https://www.aureliusfoundation.com/events/webinar-170720-s2c3l-eh844-ent3c-t39ta 3. ‘Marcus Aurelius and Journaling’, Stoicon-x Journaling with the Stoics, Sunday 1st November, register at https://www.subscribepage.com/stoiconxsalon 4. ‘’How to Be a Stoic’, The Philosopher Webinar, Monday 2nd November, register at https://www.thephilosopher1923.org/events-sellars 5. ‘Hellenistic Philosophy as a Guide to Life’, De Nacht van de Vrijdenker Filosofiefestival, Friday 13th November, register at https://www.nachtvandevrijdenker.be

Over the last few months I have signed three new contracts for books, all of which are collaborations with others. They are (in the most likely order of completion):

1. Barlaam of Seminara on Stoic Ethics (Mohr Siebeck), with C. R. Hogg, comprising a text and translation of Barlaam’s work on Stoic ethics, along with a series of interpretative essays. 2. The Cambridge Companion to Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations (Cambridge University Press), with a chapter by myself and 10 other contributors. 3. Brill’s Companion to Musonius Rufus (Brill), co-edited with Liz Gloyn, my colleague at Royal Holloway, and many, many contributors.  I’ve just had an article published, entitled ‘Renaissance Humanism and Philosophy as a Way of Life’. This has been kicking around for a while; its first outing was at a conference in Italy in 2015, and I read it more recently at a conference in London I co-organized in 2019. It has been published in a special issue of Metaphilosophy devoted to the theme of philosophy as a way of life. Due to an existing agreement between Royal Holloway and Wiley, it has been published open access. It’s part of a larger project I’ve been working on over the last few years on this topic. I have recently sent off two other papers that complement it, both of which will appear as chapters in edited volumes. The first looks at the Renaissance interest in biographies of ancient philosophers and what that might tell us about how they conceived philosophy in the period (‘Philosophical Lives in the Renaissance’). The second looks at works of philosophical consolation in the Renaissance and again what that might tell us about how they understood philosophy (‘Renaissance Consolations: Philosophical Remedies for Fate and Fortune’). I’ve had tentative plans to try to develop a book on this topic, building on these three preliminary papers. A much earlier paper on spiritual exercises in Justus Lipsius could also feed into it (here). I have not fully decided either way, but even so these three new pieces together try to make the case for the claim that during the Renaissance a number of thinkers embraced the idea of philosophy as a way of life, and by acknowledging this we can make better sense of what they were doing. Last year, my colleague Liz Gloyn and I organized a workshop on the Stoic philosopher Musonius Rufus (and off the back of that we'll be editing a volume on Musonius). This year we are organizing a second workshop, this time focused on early Stoic ethics. We hope that this will become an annual 'Royal Holloway Stoicism Workshop'. For further details and the call for papers, see the PhilEvents page.

I am very pleased to announce an event I’m involved in that will take place in March. It will be the inaugural event of The Aurelius Foundation, a new non-profit organization. The Foundation’s goals are:

Its first event will take place in Mayfair, London on 6th March 2020. This event will be an opportunity for people to learn more about the basic ideas behind Stoicism and to hear from people who apply Stoicism in a variety of personal and business contexts - from professional sport to prisons to business and finance. The goal of the event is to offer guidance and support for people at the outset of their adult and professional lives in the 18 to 30 age group. It hopes to bring together university students, recent graduates, and young entrepreneurs in order to foster useful networks for the future. The all day event - completely free - will be in central London (W1). Refreshments will be provided throughout the day. Further details about the Foundation will be available shortly at www.aureliusfoundation.com. In order to register for a place email [email protected] with ‘Aurelius Foundation Event’ in the subject line. Want to know more about Stoicism? Start here: https://theconversation.com/want-to-be-happy-then-live-like-a-stoic-for-a-week-103117 I’ve got a couple of talks coming up in 2020:

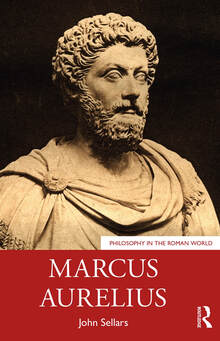

Before both, I’ll also be presenting at the inaugural event of The Aurelius Foundation, 6th March, in London. I have just finished writing a book on Marcus Aurelius. This has been a longstanding commitment so I am pleased to have finally got it finished. It is due to be published by Routledge, in their series Philosophy in the Roman World.

The aim of the book is to defend Marcus Aurelius as a philosopher, and in particular a Stoic philosopher. It is all too common to hear it said that Marcus wasn’t really a philosopher at all - he was merely an amateur, he just wrote moral exhortation, he was a confused eclectic, he resorted to colourful images and rhetoric rather than argument, and so on. I try to defend Marcus from these sorts of charges on a number of fronts. The first is biographical, where I look at Marcus’s early commitment to philosophy and his education. It is striking that the vast majority of his teachers in philosophy were Stoics. The correspondence with Fronto is especially interesting here, as it makes clear that Marcus was reading Chrysippus and Seneca, not just Epictetus. The second front is literary. The Meditations is an anomalous text. In order to take it seriously as a work of philosophy we need to understand what type of text it is and what it was supposed to achieve. That requires thinking about the idea of written exercises conceived as a form of philosophical training, which was in turn part of philosophy understood as an art of living. The third, and most important, front is philosophical. This involves looking at the philosophical themes in the Meditations and unpacking the Stoic doctrines presupposed by Marcus’s personal notes to himself. Against a common view that the Meditations is a work of practical ethics, I look at themes in logic, physics, and ethics. As I have presented it in the book, it’s in fact physical themes that predominate, although on so many topics one can see logical, physical, and ethical material intermingled. Marcus certainly engages with a wide range of philosophical material. In the process of writing the book I have found a number of things: It’s often been claimed that Marcus was not a proper philosopher because he resorted to colourful rhetorical imagery rather than giving real arguments. In fact there are quite a few arguments in the Meditations, and they are specifically Stoic arguments. For instance, in 5.16 he uses the first Stoic indemonstrable syllogism; in 7.75 he uses the fifth indemonstrable; in 10.6 he uses the second indemonstrable; and there are many other examples. The division of the books of the Meditations into sections that everyone uses today only dates back to Thomas Gataker’s edition of 1652. Earlier editions (Sally 1626, Casaubon 1643) divide things up differently, while the first printed edition (Xylander 1559) just prints each book as continuous text without divisions. When reading the Meditations, then, it would be a mistake to approach it as a series of isolated aphorisms. Often a passage that can seem cryptic makes a lot more sense when read as part of a chain of thought spanning a series of interconnected sections. The text is a thought process, not a set of carefully crafted literary nuggets. While I have learned a lot from reading Pierre Hadot’s various writings on Marcus, I have become less convinced by his claim that Epictetus’s three areas of study (topoi) are the key to understanding the Meditations. While there are certainly lots of echoes of Epictetus there, there are also lots of echoes of Seneca, but just as important are core Stoic ideas originating in the early Stoa. Marcus certainly read his Chrysippus, as were so many of his contemporaries, such as Galen, Plutarch, and Aulus Gellius. The table of contents for the book looks like this: Introduction Part I: Marcus and his Meditations 1. Marcus the Stoic Philosopher 2. The Meditations, a Philosophical Text Part II: Logic 3. Impressions and Judgements Part III: Physics 4. Nature and Change 5. Fate and Providence 6. Soul and Emotion 7. Time and Death Part IV: Ethics 8. Virtue and Justice 9. The Cosmic City Conclusion |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed